Tutankhamun

| Tutankhamun | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tutankhamen, Tutankhaten, Tutankhamon[1] possibly Nibhurrereya (as referenced in the Amarna letters) | |||

Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy, the popular icon for ancient Egypt at The Egyptian Museum. | |||

| Pharaoh | |||

| Reign | ca. 1332–1323 BC | ||

| Predecessor | Smenkhkare or Neferneferuaten | ||

| Successor | Ay | ||

| |||

| Consort | Ankhesenamun | ||

| Children | Two stillborn daughters | ||

| Father | Akhenaten[2] | ||

| Mother | "The Younger Lady" | ||

| Born | ca. 1341 BC | ||

| Died | ca. 1323 BC (aged ca. 18) | ||

| Burial | KV62 | ||

| Dynasty | 18th Dynasty | ||

Tutankhamun (alternatively spelled with Tutenkh-, -amen, -amon) was an Egyptian pharaoh of the 18th dynasty (ruled ca. 1332 BC – 1323 BC in the conventional chronology), during the period of Egyptian history known as the New Kingdom. He is popularly referred to as King Tut. His original name, Tutankhaten, means "Living Image of Aten", while Tutankhamun means "Living Image of Amun". In hieroglyphs, the name Tutankhamun was typically written Amen-tut-ankh, because of a scribal custom that placed a divine name at the beginning of a phrase to show appropriate reverence.[3] He is possibly also the Nibhurrereya of the Amarna letters, and likely the 18th dynasty king Rathotis who, according to Manetho, an ancient historian, had reigned for nine years—a figure that conforms with Flavius Josephus's version of Manetho's Epitome.[4]

The 1922 discovery by Howard Carter and George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon[5][6] of Tutankhamun's nearly intact tomb received worldwide press coverage. It sparked a renewed public interest in ancient Egypt, for which Tutankhamun's burial mask, now in Cairo Museum, remains the popular symbol. Exhibits of artifacts from his tomb have toured the world. In February 2010, the results of DNA tests confirmed that he was the son of Akhenaten (mummy KV55) and Akhenaten's sister and wife (mummy KV35YL), whose name is unknown but whose remains are positively identified as "The Younger Lady" mummy found in KV35.[7]

Life

Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten (formerly Amenhotep IV) and one of Akhenaten's sisters,[8] or perhaps one of his cousins.[9] As a prince he was known as Tutankhaten.[10] He ascended to the throne in 1333 BC, at the age of nine or ten, taking the throne name Nebkheperure.[11] His wet-nurse was a woman called Maia, known from her tomb at Saqqara.[12]

When he became king, he married his half-sister, Ankhesenpaaten, who later changed her name to Ankhesenamun. They had two daughters, both stillborn.[7] Computed tomography studies released in 2011 revealed that one daughter died at 5–6 months of pregnancy and the other at 9 months of pregnancy. No evidence was found in either mummy of congenital anomalies or an apparent cause of death.[13]

Reign

Given his age, the king probably had very powerful advisers, presumably including General Horemheb and the Vizier Ay. Horemheb records that the king appointed him "lord of the land" as hereditary prince to maintain law. He also noted his ability to calm the young king when his temper flared.[14]

Domestic policy

In his third regnal year, Tutankhamun reversed several changes made during his father's reign. He ended the worship of the god Aten and restored the god Amun to supremacy. The ban on the cult of Amun was lifted and traditional privileges were restored to its priesthood. The capital was moved back to Thebes and the city of Akhetaten abandoned.[15] This is when he changed his name to Tutankhamun, "Living image of Amun", reinforcing the restoration of Amun.

As part of his restoration, the king initiated building projects, in particular at Thebes and Karnak, where he dedicated a temple to Amun. Many monuments were erected, and an inscription on his tomb door declares the king had "spent his life in fashioning the images of the gods". The traditional festivals were now celebrated again, including those related to the Apis Bull, Horemakhet, and Opet. His restoration stela says:

The temples of the gods and goddesses ... were in ruins. Their shrines were deserted and overgrown. Their sanctuaries were as non-existent and their courts were used as roads ... the gods turned their backs upon this land ... If anyone made a prayer to a god for advice he would never respond.[16]

Foreign policy

The country was economically weak and in turmoil following the reign of Akhenaten. Diplomatic relations with other kingdoms had been neglected, and Tutankhamun sought to restore them, in particular with the Mitanni. Evidence of his success is suggested by the gifts from various countries found in his tomb. Despite his efforts for improved relations, battles with Nubians and Asiatics were recorded in his mortuary temple at Thebes. His tomb contained body armor and folding stools appropriate for military campaigns. However, given his youth and physical disabilities, which seemed to require the use of a cane in order to walk (he died c. age 19), historians speculate that he did not personally take part in these battles.[7][17]

Health and appearance

Tutankhamun was slight of build, and was roughly 180 cm (5 ft 11 in) tall.[18] He had large front incisors and the overbite characteristic of the Thutmosid royal line to which he belonged. Between September 2007 and October 2009, various mummies were subjected to detailed anthropological, radiological, and genetic studies as part of the King Tutankhamun Family Project. It was determined that none of the mummies of the Tutankhamun lineage has a cephalic index of 75 or less (indicating dolichocephaly), that Tutankhamun actually has a cephalic index of 83.9, indicating brachycephaly, and that none of their skull shapes can be considered pathological.[19] The research also showed that Tutankhamun had "a slightly cleft palate"[20] and possibly a mild case of scoliosis, a medical condition in which the spine is curved from side to side.

Probable product of incest

According to the September 2010 issue of National Geographic magazine, Tutankhamun was the result of an incestuous relationship and, because of that, may have suffered from several genetic defects that contributed to his early death.[21] For years, scientists have tried to unravel ancient clues as to why the boy king of Egypt, who reigned for 10 years, died at the age of 19. Several theories have been put forth; one was that he was killed by a blow to the head, while another was that his death was caused by a broken leg.

Various diseases invoked as possible explanations to his early demise included Marfan syndrome, Wilson-Turner X-linked mental retardation syndrome, Fröhlich syndrome (adiposogenital dystrophy), Klinefelter syndrome, androgen insensitivity syndrome, aromatase excess syndrome in conjunction with sagittal craniosynostosis syndrome, Antley–Bixler syndrome or one of its variants[22] and temporal lobe epilepsy.[23]

In June 2010, German scientists said they believed there was evidence that he died of sickle cell disease. However, other experts have rejected the hypothesis of homozygous sickle cell disease[24] based on logics based on survival beyond 5 year age and the location of the osteonecrosis which is characteristic of Freiberg-Kohler syndrome rather than sickle-cell disease. Research conducted in 2005 by archaeologists, radiologists, and geneticists who started performing CT scans on his mummy found that he was not killed by a blow to the head, as previously thought.[21] New CT images discovered congenital flaws, which are more common among the children of incest. Siblings are more likely to pass on twin copies of harmful genes, which is why children of incest more commonly manifest genetic defects.[25] It is suspected he also had a partially cleft palate, another congenital defect.[26]

By 2008, the team began DNA research on Tutankhamun and the mummified remains of other members of his family. The results from the DNA samples finally put to rest questions about Tutankhamun's lineage, proving that his father was Akhenaten, but that his mother was not one of Akhenaten's known wives. His mother was one of his father's five sisters, although it is not known which one.[25] The team was able to establish with a probability of better than 99.99 percent that Amenhotep III was the father of the individual in KV55, who was in turn the father of Tutankhamun.[27] The young king's mother was found through the DNA testing of a mummy designated as 'The Younger Lady' (KV35YL), which was found lying beside Queen Tiye in the alcove of KV35. Her DNA proved that, like his father, she was a child of Amenhotep III and Tiye; thus, Tutankhamun's parents were brother and sister.[28] Queen Tiye held much political influence at court and acted as an adviser to her son after the death of her husband. Some geneticists dispute these findings, however, and "complain that the team used inappropriate analysis techniques."[29]

While the data are still incomplete, the study suggests that one of the mummified fetuses found in Tutankhamun's tomb is the daughter of Tutankhamun himself, and the other fetus is probably his child as well. So far, only partial data for the two female mummies from KV21 has been obtained.[30] One of them, KV21A, may well be the infants' mother and thus, Tutankhamun's wife, Ankhesenamun. It is known from history that she was the daughter of Akhenaten and Nefertiti, and thus likely to be her husband's half-sister. Another consequence of inbreeding can be children whose genetic defects do not allow them to be brought to term.

The research team consisted of Egyptian scientists Yehia Gad and Somaia Ismail from the National Research Centre in Cairo. The CT scans were conducted under the direction of Ashraf Selim and Sahar Saleem of the Faculty of Medicine at Cairo University. Three international experts served as consultants: Carsten Pusch of the Eberhard Karls University of Tübingen, Germany; Albert Zink of the EURAC-Institute for Mummies and the Iceman in Bolzano, Italy;[31] and Paul Gostner of the Central Hospital Bolzano.[32] STR analysis based DNA fingerprinting analysis combined with the other techniques have rejected the hypothesis of gynecomastia and craniosynostoses (e.g., Antley-Bixler syndrome) or Marfan syndrome, but an accumulation of malformations in Tutankhamun's family was evident. Several pathologies including Köhler disease II were diagnosed in Tutankhamun; none alone would have caused death. Genetic testing for STEVOR, AMA1, or MSP1 genes specific for Plasmodium falciparum revealed indications of malaria tropica in 4 mummies, including Tutankhamun's.[33] However their exact contribution to the causality of his death still is highly debated.

As stated above, the team discovered DNA from several strains of a parasite proving he was infected with the most severe strain of malaria several times in his short life. Malaria can trigger circulatory shock or cause a fatal immune response in the body, either of which can lead to death. If Tutankhamun did suffer from a bone disease which was crippling, it may not have been fatal. "Perhaps he struggled against other [congenital flaws] until a severe bout of malaria or a leg broken in an accident added one strain too many to a body that could no longer carry the load," wrote Zahi Hawass, archeologist and head of Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquity involved in the research.

A review of the medical findings to date found that he suffered from mild kyphoscoliosis, pes planus, hypophalangism of the right foot, bone necrosis of second and third metatarsal bones of the left foot, malaria and a complex fracture of the right knee shortly before death.[34]

Death

There are no surviving records of Tutankhamun's final days. What caused Tutankhamun's death has been the subject of considerable debate. Major studies have been conducted in an effort to establish the cause of death.

Although there is some speculation that Tutankhamun was assassinated, the consensus is that his death was accidental. A CT scan taken in 2005 shows that he had suffered a left leg fracture[35] shortly before his death, and that the leg had become infected. DNA analysis conducted in 2010 showed the presence of malaria in his system, leading to the belief that malaria and Köhler disease II combined led to his death.[36] On September 14, 2012, ABC News presented a theory about Tutankhamun's death from lecturer and surgeon Dr. Hutan Ashrafian, who believed that temporal lobe epilepsy caused the fatal fall which broke Tutankhamun's leg.[23]

Finally in late 2013, Egyptologist Dr. Chris Naunton and scientists from the Cranfield Institute performed a "virtual autopsy" of the boy king, revealing a pattern of injuries down one side of his body. Car-crash investigators then created computer simulations of chariot accidents. Dr. Naunton concluded Tutankhamun was killed in a chariot crash: a chariot smashed into him while he was on his knees, shattering his ribs and pelvis. As well, Dr. Naunton referenced Howard Carter's records of the body having been burnt. Working with anthropologist Dr. Robert Connolly and forensic archaeologist Dr. Matthew Ponting, they produced evidence that Tutankhamun's body was burnt while sealed inside his coffin. Embalming oils combined with oxygen and linen had caused a chemical reaction, creating temperatures of more than 200 °C. Dr. Naunton said, "The charring and possibility that a botched mummification led to the body spontaneously combusting shortly after burial was entirely unexpected."[37][38]

Aftermath of death

With the death of Tutankhamun and the two stillborn children buried with him, the Thutmosid family line came to an end. The Amarna letters indicate that Tutankhamun's wife, recently widowed, wrote to the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I, asking if she could marry one of his sons. The letters do not say how Tutankhamun died. In the message to the Hittite king, Ankhesenamun says that she was very afraid, but would not take one of her own people as husband. However, the son was killed before reaching his new wife. Shortly afterward Ay married Tutankhamun's widow and became Pharaoh as a war between the two countries was fought, and Egypt was left defeated.[39] The fate of Ankhesenamun is not known, but she disappears from record and Ay's second wife Tey became Great Royal Wife. After Ay's death, Horemheb usurped the throne and instigated a campaign of damnatio memoriae against him. Tutankhamun's father Akhenaten, stepmother Nefertiti, his wife Ankhesenamun, half sisters and other family members were also included. Not even Tutankhamun was spared. His images and cartouches were also erased. Horemheb himself, despite a possible marriage to Nefertiti's sister, Mutnedjmet, was left childless and willed the throne to Paramessu, who founded the Ramesside family line of pharaohs.

"Perfect God, Lord of the Two Lands"–('Ntr-Nfr, Neb-taui' - right to left)

Significance

Tutankhamun was nine years old when he became Pharaoh, son of god Ra, and reigned for approximately ten years. "The Egyptian sun god Ra, considered the father of all pharaohs, was said to have created himself from a pyramid-shaped mound of earth before creating all other gods." (Donald B. Redford, Ph.D., Penn State) [40]

In historical terms, Tutankhamun's significance stems from the fact that his reign was close to the apogee of Egypt as a world power and from his rejection of the radical religious innovations introduced by his predecessor and father, Akhenaten.[41] Secondly, his tomb in the Valley of the Kings was discovered by Carter almost completely intact—the most complete ancient Egyptian royal tomb ever found. As Tutankhamun began his reign at such an early age, his vizier, and eventual successor Ay, was probably making most of the important political decisions during Tutankhamun's reign.

Kings were venerated after their deaths through mortuary cults and associated temples. Tutankhamun was one of the few kings worshiped in this manner during his lifetime.[42] A stela discovered at Karnak and dedicated to Amun-Ra and Tutankhamun indicates that the king could be appealed to in his deified state for forgiveness and to free the petitioner from an ailment caused by sin. Temples of his cult were built as far away as in Kawa and Faras in Nubia. The title of the sister of the Viceroy of Kush included a reference to the deified king, indicative of the universality of his cult.[43]

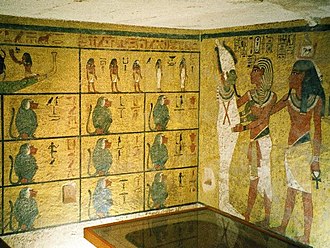

Tomb

Tutankhamun was buried in a tomb that was small relative to his status. His death may have occurred unexpectedly, before the completion of a grander royal tomb, so that his mummy was buried in a tomb intended for someone else. This would preserve the observance of the customary seventy days between death and burial.[44]

King Tutankhamun's mummy still rests in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings. On 4 November 2007, 85 years to the day after Carter's discovery, the 19-year-old pharaoh went on display in his underground tomb at Luxor, when the linen-wrapped mummy was removed from its golden sarcophagus to a climate-controlled glass box. The case was designed to prevent the heightened rate of decomposition caused by the humidity and warmth from tourists visiting the tomb.[45]

Forgotten

Tutankhamun seems to have faded from public consciousness in Ancient Egypt within a short time after his death, and remained virtually unknown until the 1920s. His tomb was robbed at least twice in antiquity, but based on the items taken (including perishable oils and perfumes) and the evidence of restoration of the tomb after the intrusions, it seems clear that these robberies took place within several months at most of the initial burial. Eventually the location of the tomb was lost because it had come to be buried by stone chips from subsequent tombs, either dumped there or washed there by floods. In the years that followed, some huts for workers were built over the tomb entrance, clearly not knowing what lay beneath. When at the end of the 20th Dynasty the Valley of the Kings burials were systematically dismantled, the burial of Tutankhamun was overlooked, presumably because knowledge of it had been lost and his name may have been forgotten.

Curse

For many years, rumors of a "Curse of the Pharaohs" (probably fueled by newspapers seeking sales at the time of the discovery[46]) persisted, emphasizing the early death of some of those who had entered the tomb. However, a recent study of journals and death records indicated no statistical difference between the age of death of those who entered the tomb and those on the expedition who did not.

In popular culture

If Tutankhamun is the world's best known pharaoh, it is largely because his tomb is among the best preserved, and his image and associated artifacts the most-exhibited. As Jon Manchip White writes, in his foreword to the 1977 edition of Carter's The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun, "The pharaoh who in life was one of the least esteemed of Egypt's Pharoahs has become in death the most renowned."

The discoveries in the tomb were prominent news in the 1920s. Tutankhamen came to be called by a modern neologism, "King Tut". Ancient Egyptian references became common in popular culture, including Tin Pan Alley songs; the most popular of the latter was "Old King Tut" by Harry Von Tilzer from 1923, which was recorded by such prominent artists of the time as Jones & Hare and Sophie Tucker. "King Tut" became the name of products, businesses, and even the pet dog of U.S. President Herbert Hoover.

The interest in this tomb and its alleged "curse" also led to horror movies featuring a vengeful mummy.

Exhibitions

Relics from Tutankhamun's tomb are among the most traveled artifacts in the world. They have been to many countries, but probably the best-known exhibition tour was The Treasures of Tutankhamun tour, which ran from 1972 to 1979. This exhibition was first shown in London at the British Museum from 30 March until 30 September 1972. More than 1.6 million visitors saw the exhibition, some queuing for up to eight hours. It was the most popular exhibition in the Museum's history.[citation needed] The exhibition moved on to many other countries, including the USA, USSR, Japan, France, Canada, and West Germany. The Metropolitan Museum of Art organized the U.S. exhibition, which ran from 17 November 1976 through 15 April 1979. More than eight million attended.

In 2004, the tour of Tutankhamun funerary objects entitled Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter, consisting of fifty artifacts from Tutankhamun's tomb and seventy funerary goods from other 18th Dynasty tombs, began in Basle, Switzerland and went on to Bonn Germany on the second leg of the tour. This European tour was organised by the Art and Exhibition Hall of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Supreme Council of Antiquities (SCA), and the Egyptian Museum in cooperation with the Antikenmuseum Basel and Sammlung Ludwig. Deutsche Telekom sponsored the Bonn exhibition.[47]

In 2005, Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities, in partnership with Arts and Exhibitions International and the National Geographic Society, launched a tour of Tutankhamun treasures and other 18th Dynasty funerary objects, this time called Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. It features the same exhibits as Tutankhamen: The Golden Hereafter in a slightly different format. It was expected to draw more than three million people.[48]

The exhibition started in Los Angeles, then moved to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, Chicago and Philadelphia. The exhibition then moved to London[49] before finally returning to Egypt in August 2008. An encore of the exhibition in the United States ran at the Dallas Museum of Art from October 2008 to May 2009.[50] The tour continued to other U.S. cities.[51] After Dallas the exhibition moved to the de Young Museum in San Francisco, followed by the Discovery Times Square Exposition in New York City.[52]

In 2011 the exhibition visited Australia for the first time, opening at the Melbourne Museum in April for its only Australian stop before Egypt's treasures return to Cairo in December, 2011.[53]

The exhibition includes 80 exhibits from the reigns of Tutankhamun's immediate predecessors in the Eighteenth dynasty, such as Hatshepsut, whose trade policies greatly increased the wealth of that dynasty and enabled the lavish wealth of Tutankhamun's burial artifacts, as well as 50 from Tutankhamun's tomb. The exhibition does not include the gold mask that was a feature of the 1972–1979 tour, as the Egyptian government has determined that the mask is too fragile to withstand travel and will never again leave the country.[54]

A separate exhibition called Tutankhamun and the World of the Pharaohs began at the Ethnological Museum in Vienna from 9 March to 28 September 2008, showing a further 140 treasures.[55] Renamed Tutankhamun: The Golden King and the Great Pharaohs, this exhibition began a tour of the US and Canada in Atlanta on 15 November 2008. It is scheduled to finish in Seattle on 6 January 2013.[56]

Film and television

- We Want Our Mummy, a 1939 film by The Three Stooges. In it, the slapstick comedy trio explores the tomb of the midget King Rutentuten (pronounced "rootin'-tootin'") and his Queen, Hotsy Totsy. A decade later, they were crooked used-chariot salesmen in Mummy's Dummies, in which they ultimately assist a different King Rootentootin (Vernon Dent) with a toothache.

- King Tut, played by Victor Buono, was a villain on the Batman TV series which aired from 1966 to 1968. Mild-mannered Egyptologist William Omaha McElroy, after suffering a concussion, came to believe he was the reincarnation of Tutankhamun. His response to this knowledge was to embark upon a crime spree that required him to fight against the "Caped Crusaders", Batman and Robin.

- The Discovery Kids animated series Tutenstein stars a fictional mummy based on Tutankhamun, named Tutankhensetamun and nicknamed Tutenstein in his afterlife. He is depicted as a lazy and spoiled 10-year-old mummy boy who must guard a magical artifact called the Scepter of Was from the evil Egyptian god Set.

- The first episode of the 2005 BBC series Egypt: Rediscovering a Lost World focuses on the life and death of Tutankhamun and the serendipitous discovery of his tomb.

- La Reine Soleil (2007 animated film by Philippe Leclerc), features Akhenaten, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun), Akhesa (Ankhesenepaten, later Ankhesenamun), Nefertiti, and Horemheb in a complex struggle pitting the priests of Amun against Akhenaten's intolerant monotheism.

- In the US documentary series, King Tut Unwrapped, Moroccan singer-actor, Faissal Oberon Azizi, portrayed Tutankhamun.

Other media

- "King Tut", a whimsical 1978 song by (American comedian) "Steve Martin and the Toot Uncommons" (a backup group consisting of members of the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band).

- The 1981 arcade game Tutankham revolves around King Tutankhamun.

- 1989 television networks often advertised commercials for King Tuts dog food, complete with Anubis-styled canine animation and music to the tune of "Camel Caravan." The can label was also adorned with themed hieroglyphs.

- The mummy of Tutankhamun is depicted as a villain in Raj Comics's Nagraj, a Hindi superhero comicbook. In this series, his mask is the source of his power.

- For "Transformers" the Decepticon character Frenzy repeats the name, "Tutankhamun."

- The video game Sphinx and the Cursed Mummy features a fictional representation of Prince Tutankhamun. Tutankhamun is the victim of an unnamed magical ritual which results in almost instantaneous mummification and extraction of what appears to be his "life force". In the instruction manual, the Mummy is described as young, inexperienced and naive.

- The novel Tutankhamun (2008) by novelist Nick Drake [not the musician] takes place during the reign of Tutankhamun and gives a possible explanation for his injury and death (and the aftermath) set amid a murder mystery.

- The novel The Lost Queen of Egypt (1937) by novelist Lucile Morrison is about Ankhsenpaaten / Ankhesenamun, the wife of Tutankhamun. He is a major character, coming in about midway in the story. Here, his name is spelled as 'Tutankhamon.' It's strongly hinted that he was murdered.

Names

| Horus name |

|

𓅃𓃒𓂡𓏏𓅱𓏏𓄟𓋴𓏏𓅱𓏪𓊁 Kanakht Tutmesut The strong bull, pleasing of birth | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nebti name |

|

𓅒𓄤𓉔𓊪𓅱𓇩𓏪𓋴𓎼𓂋𓎛𓂝𓇿𓇿𓈅𓈅𓅨𓉥𓉐𓏤𓇋𓏠𓈖𓎟𓂋𓇥𓂋𓀯 Neferhepusegerehtawy Werahamun Nebrdjer One of perfect laws, who pacifies the two lands; Great of the palace of Amun; Lord of all[57] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Horus name |

|

𓅉𓍞𓈍𓏥𓊃𓊵𓏏𓊪𓊹𓊹𓊹𓋾𓈎𓏛𓁦𓋴𓊵𓏏𓊪𓊹𓊹𓊹𓅱𓍿𓊃𓍞𓈍𓏥𓇋𓏏𓆑𓀯𓆑𓁛𓍞𓈍𓏥𓋭𓊃𓇾𓇾𓅓 Wetjeskhausehetepnetjeru Heqamaatsehetepnetjeru Wetjeskhauitefre Wetjeskhautjestawyim Who wears crowns and pleases the gods; Ruler of Truth, who pleases the gods; Who wears the crowns of his father, Re; Who wears crowns, and binds the two lands therein | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Prenomen |

|

𓇓𓆤 𓍹𓇳𓆣𓏥𓎟𓍺 Nebkheperure Lord of the forms of Re | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Son of Re |

|

𓅭𓇳 𓍹𓇋𓏠𓈖𓏏𓅱𓏏𓋹𓋾𓉺𓇗𓍺 Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema Living Image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis |

At the reintroduction of traditional religious practice, his name changed. It is transliterated as twt-ˤnḫ-ỉmn ḥq3-ỉwnw-šmˤ, and according to modern Egyptological convention is written Tutankhamun Hekaiunushema, meaning "Living image of Amun, ruler of Upper Heliopolis". On his ascension to the throne, Tutankhamun took a praenomen. This is transliterated as nb-ḫprw-rˤ, and, again, according to modern Egyptological convention is written Nebkheperure, meaning "Lord of the forms of Re". The name Nibhurrereya in the Amarna letters may be closer to how his praenomen was actually pronounced.

References

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. (2006). Chronicle of the Pharaohs: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. p. 128. ISBN 0-500-28628-0.

- ^ Frail boy-king Tut died from malaria, broken leg[dead link] by Paul Schemm, Associated Press. 16 February 2010.

- ^ Zauzich, Karl-Theodor (1992). Hieroglyphs Without Mystery. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-0-292-79804-5.

- ^ "Manetho's King List".

- ^

"The Egyptian Exhibition at Highclere Castle". Archived from the original on 3 September 2010. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hawass, Zahi A. The golden age of Tutankhamun: divine might and splendor in the New Kingdom. American Univ in Cairo Press, 2004.

- ^ a b c Hawass, Zahi (17 February 2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 638–647. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hawass, Zahi (17 February 2010). "Ancestry and Pathology in King Tutankhamun's Family". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 303 (7): 640–641. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Powell, Alvin (12 February 2013). "A different take on Tut". Harvard Gazette. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

- ^ Jacobus van Dijk. "The Death of Meketaten" (PDF). p. 7. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- ^ "Classroom TUTorials: The Many Names of King Tutankhamun" (pdf). Michael C. Carlos Museum. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- ^ "Egypt Update: Rare Tomb May Have Been Destroyed". Science Mag. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Hawass, Zahi and Saleem, Sahar N. Mummified daughters of King Tutankhamun: Archaeological and CT studies. The American Journal of Roentgenology 2011. Vol 197, No. 5, pp. W829-836.

- ^ Booth pp. 86–87

- ^ Erik Hornung, Akhenaten and the Religion of Light, Translated by David Lorton, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2001, ISBN 0-8014-8725-0.

- ^ Hart, George (1990). Egyptian Myths. University of Texas Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-292-72076-9.

- ^ Booth pp. 129–130

- ^ "Radiologists Attempt To Solve Mystery Of Tut's Demise" from ScienceDaily.com

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1001/jama.2010.121, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1001/jama.2010.121instead. - ^ Handwerk, Brian (8 March 2005). "King Tut Not Murdered Violently, CT Scans Show". National Geographic News. p. 2. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Markel, H. (17 February 2010). "King Tutankhamun, modern medical science, and the expanding boundaries of historical inquiry". JAMA. 303 (7): 667–668. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) (subscription required) - ^ a b

Rosenbaum, Matthew (14 September 2012). "Mystery of King Tut's death solved?". ABC News. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^

Pays, JF (December 2010). "Tutankhamun and sickle-cell anaemia". Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 103 (5, number 5): 346–347. doi:10.1007/s13149-010-0095-3. PMID 20972847. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)(Abstract) - ^ a b Bates, Claire (20 February 2010). "Unmasked: The real faces of the crippled King Tutankhamun (who walked with a cane) and his incestuous parents". Daily Mail. London.

- ^ "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "DNA experts disagree over Tutankhamun's ancestry". Archaeology News Network. 22 January 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- ^ "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "EURAC research – Research – Institutes – Institute for Mummies and the Iceman – Home". Eurac.edu. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ "King Tut's Family Secrets – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 11 October 2010.

- ^ JAMA. 2010 Feb 17;303(7):638-47. Ancestry and pathology in King Tutankhamun's family. Hawass Z, Gad YZ, Ismail S, Khairat R, Fathalla D, Hasan N, Ahmed A, Elleithy H, Ball M, Gaballah F, Wasef S, Fateen M, Amer H, Gostner P, Selim A, Zink A, Pusch CM. Source Supreme Council of Antiquities, Cairo, Egypt. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20159872.1

- ^ Hussein K, Matin E, Nerlich AG (2013) Paleopathology of the juvenile Pharaoh Tutankhamun-90th anniversary of discovery. Virchows Arch

- ^ Hawass, Zahi. "Tutankhamon, segreti di famiglia". National Geographic. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Roberts, Michelle (16 February 2010). "'Malaria' killed King Tutankhamun". BBC News. Retrieved 12 March 2010.

- ^ Owen, Jonathan (3 November 2013). "Solved: The mystery of King Tutankhamun's death". The Independent. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Webb, Sam (2 November 2013). "Mummy-fried! Tutankhamun's body spontaneously combusted inside his coffin following botched embalming job after he died in speeding chariot accident". The Daily Mail. Retrieved 3 November 2013.

- ^ Interview with G.A. Gaballa, of Cairo University. "The Hittites: A Civilization that Changed the World" by Cinema Epoch 2004. Directed by Tolga Ornek. Documentary.

- ^ Redford, Donald B., Ph.D.; McCauley, Marissa. "How were the Egyptian pyramids built?". Research. The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aude Gros de Beler, Tutankhamun, foreword Aly Maher Sayed, Moliere, ISBN 2-84790-210-4

- ^ Oxford Guide: Essential Guide to Egyptian Mythology, Editor Donald B. Redford, p. 85, Berkley, ISBN 0-425-19096-X

- ^ The Boy Behind the Mask, Charlotte Booth, p. 120, Oneworld, 2007, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- ^ "The Golden Age of Tutankhamun: Divine Might and Splendour in the New Kingdom", Zahi Hawass, p. 61, American University in Cairo Press, 2004, ISBN 977-424-836-8

- ^ Michael McCarthy (5 October 2007). "3,000 years old: the face of Tutankhaten". The Independent. London.

- ^ Hankey, Julie (2007). A Passion for Egypt: Arthur Weigall, Tutankhamun and the 'Curse of the Pharaohs'. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-1-84511-435-0.

- ^ "Al-Ahram Weekly | Heritage | Under Tut's spell". Weekly.ahram.org.eg. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ "King Tut exhibition. Tutankhamun & the Golden Age of the Pharaohs. Treasures from the Valley of the Kings". Arts and Exhibitions International. Retrieved 5 August 2006.[dead link]

- ^ Return of the King (Times Online)[dead link]

- ^ "Dallas Museum of Art Website". Dallasmuseumofart.org. Retrieved 18 July 2009.

- ^ Associated Press, "Tut Exhibit to Return to US Next Year[dead link]"

- ^ "Tutankhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs | King Tut Returns to San Francisco, June 27, 2009 – March 28, 2010". Famsf.org. Retrieved 18 July 2009. [dead link]

- ^ Melbourne Museum's Tutenkhamun and the Golden Age of the Pharaoh's Official Site[dead link]

- ^ Jenny Booth (6 January 2005). "CT scan may solve Tutankhamun death riddle". The Times. London.

- ^ Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna[dead link]

- ^ "King Tut: The Exhibition | King Tut | Special Exhibits". Pacificsciencecenter.org. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- ^ "Digital Egypt for Universities: Tutankhamun". University College London. 22 June 2003. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

Further reading

- Andritsos, John. Social Studies of ancient Egypt: Tutankhamun. Australia 2006

- Booth, Charlotte. The Boy Behind the Mask", Oneworld, ISBN 978-1-85168-544-8

- Brier, Bob. The Murder of Tutankhamun: A True Story. Putnam Adult, 13 April 1998, ISBN 0-425-16689-9 (paperback)/ISBN 0-399-14383-1 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-613-28967-6 (School & Library Binding)

- Carter, Howard and Arthur C. Mace, The Discovery of the Tomb of Tutankhamun. Courier Dover Publications, 1 June 1977, ISBN 0-486-23500-9 The semi-popular account of the discovery and opening of the tomb written by the archaeologist responsible

- Desroches-Noblecourt, Christiane. Sarwat Okasha (Preface), Tutankhamun: Life and Death of a Pharaoh. New York: New York Graphic Society, 1963, ISBN 0-8212-0151-4 (1976 reprint, hardcover) /ISBN 0-14-011665-6 (1990 reprint, paperback)

- Edwards, I.E.S., Treasures of Tutankhamun. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976, ISBN 0-345-27349-4 (paperback)/ISBN 0-670-72723-7 (hardcover)

- Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, The Mummy of Tutankhamun: the CT Scan Report, as printed in Ancient Egypt, June/July 2005.

- Haag, Michael. "The Rough Guide to Tutankhamun: The King: The Treasure: The Dynasty". London 2005. ISBN 1-84353-554-8.

- Hoving, Thomas. The search for Tutankhamun: The untold story of adventure and intrigue surrounding the greatest modern archeological find. New York: Simon & Schuster, 15 October 1978, ISBN 0-671-24305-5 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-8154-1186-3 (paperback) This book details a number of interesting anecdotes about the discovery and excavation of the tomb

- James, T. G. H. Tutankhamun. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 1 September 2000, ISBN 1-58663-032-6 (hardcover) A large-format volume by the former Keeper of Egyptian Antiquities at the British Museum, filled with colour illustrations of the funerary furnishings of Tutankhamun, and related objects

- Neubert, Otto. Tutankhamun and the Valley of the Kings. London: Granada Publishing Limited, 1972, ISBN 0-583-12141-1 (paperback) First hand account of the discovery of the Tomb

- Reeves, C. Nicholas. The Complete Tutankhamun: The King, the Tomb, the Royal Treasure. London: Thames & Hudson, 1 November 1990, ISBN 0-500-05058-9 (hardcover)/ISBN 0-500-27810-5 (paperback) Fully covers the complete contents of his tomb

- Rossi, Renzo. Tutankhamun. Cincinnati (Ohio) 2007 ISBN 978-0-7153-2763-0, a work all illustrated and coloured.