John Minton (artist): Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Misc citation tidying. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | #UCB_CommandLine |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

| training = [[St John's Wood School of Art]] |

| training = [[St John's Wood School of Art]] |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Francis John Minton''' (25 December 1917 – 20 January 1957) was an English painter, illustrator, stage designer and teacher. After studying in [[France]], he became a teacher in [[London]], and at the same time maintained a consistently large output of works. In addition to landscapes, portraits and other paintings, some of them on an unusually large scale, he built up a reputation as an illustrator of books. |

'''Francis John Minton''' (25 December 1917 – 20 January 1957) was an English painter, illustrator, stage designer and teacher. After studying in [[France]], he became a teacher in [[London]], and at the same time maintained a consistently large output of works. In addition to landscapes, portraits and other paintings, some of them on an unusually large scale, he built up a reputation as an illustrator of books. |

||

| Line 22: | Line 21: | ||

===Early years=== |

===Early years=== |

||

Minton was born in [[Great Shelford]], [[Cambridgeshire]], the second of three sons of Francis Minton, a solicitor, and his wife, Kate, ''née'' Webb.<ref name="dnb">Middleton, Michael. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35041 "Minton, (Francis) John (1917–1957)"], ''[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]]'', [[Oxford University Press]], 2004, online edition, Oct 2006, accessed 16 May 2011 {{subscription}}</ref> From 1925 to 1932, he was educated at Northcliff House, [[Bognor Regis]], [[Sussex]], and then from 1932 to 1935 at [[Reading School]].<ref name=dnb/> He studied art at [[St John's Wood School of Art]] from 1935 to 1938 |

Minton was born in [[Great Shelford]], [[Cambridgeshire]], the second of three sons of Francis Minton, a solicitor, and his wife, Kate, ''née'' Webb.<ref name="dnb">Middleton, Michael. [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35041 "Minton, (Francis) John (1917–1957)"], ''[[Oxford Dictionary of National Biography]]'', [[Oxford University Press]], 2004, online edition, Oct 2006, accessed 16 May 2011 {{subscription required}}</ref> From 1925 to 1932, he was educated at Northcliff House, [[Bognor Regis]], [[Sussex]], and then from 1932 to 1935 at [[Reading School]].<ref name=dnb/> He studied art at [[St John's Wood School of Art]] from 1935 to 1938<ref name="mg">Bone, Stephen. "John Minton – Artist of many talents," ''The Manchester Guardian'', 22 January 1957, p. 5</ref> and was greatly influenced by his fellow student [[Michael Ayrton]], who enthused him with the work of French [[neo-romanticism|neo-romantic]] painters.<ref name=dnb/> He spent eight months studying in France, frequently accompanied by Ayrton, and returned from Paris when the [[Second World War]] began. |

||

In October 1939 Minton registered as a [[conscientious objector]], but in 1941 changed his views and joined the [[Royal Pioneer Corps|Pioneer Corps]]. He was commissioned in the [[Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry]] in 1943, but was discharged on medical grounds in the same year.<ref name=dnb/> While in the army, Minton, with Ayrton, designed the costumes and scenery for [[John Gielgud]]'s 1942 production of ''[[Macbeth]]''. The settings moved the piece from the 11th century to "the age of illuminated missals";<ref>"Macbeth", ''[[The Times]]'', 9 July 1942, p. 6</ref> ''[[The Manchester Guardian]]'' wrote that they "should be long remembered".<ref name=mg/> In the same year he and Ayrton held a joint exhibition at the [[Leicester Galleries]] in London. ''[[The Times]]'' wrote, "Mr. Minton is seen to have an overcast, gloomy realism, and much intensity of feeling, which he expresses in dark colour schemes, both in a curious and effective self-portrait and in paintings of streets and bombed buildings."<ref>"Young Artists – Exhibition at Leicester Galleries''", ''The Times'', 16 October 1942, p. 6</ref> Minton's early penchant for dark colour schemes can be seen in his 1939 ''Landscape at Les Baux'', in the [[Tate Gallery]].<ref>[http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/minton-landscape-at-les-baux-t04926 "Landscape at Les Baux"], [[Tate Gallery|Tate]] Collection, accessed 25 November 2014.</ref> |

In October 1939 Minton registered as a [[conscientious objector]], but in 1941 changed his views and joined the [[Royal Pioneer Corps|Pioneer Corps]]. He was commissioned in the [[Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry]] in 1943, but was discharged on medical grounds in the same year.<ref name=dnb/> While in the army, Minton, with Ayrton, designed the costumes and scenery for [[John Gielgud]]'s 1942 production of ''[[Macbeth]]''. The settings moved the piece from the 11th century to "the age of illuminated missals";<ref>"Macbeth", ''[[The Times]]'', 9 July 1942, p. 6</ref> ''[[The Manchester Guardian]]'' wrote that they "should be long remembered".<ref name=mg/> In the same year he and Ayrton held a joint exhibition at the [[Leicester Galleries]] in London. ''[[The Times]]'' wrote, "Mr. Minton is seen to have an overcast, gloomy realism, and much intensity of feeling, which he expresses in dark colour schemes, both in a curious and effective self-portrait and in paintings of streets and bombed buildings."<ref>"Young Artists – Exhibition at Leicester Galleries''", ''The Times'', 16 October 1942, p. 6</ref> Minton's early penchant for dark colour schemes can be seen in his 1939 ''Landscape at Les Baux'', in the [[Tate Gallery]].<ref>[http://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/minton-landscape-at-les-baux-t04926 "Landscape at Les Baux"], [[Tate Gallery|Tate]] Collection, accessed 25 November 2014.</ref> |

||

| Line 36: | Line 35: | ||

Minton's posthumous fame is principally as an illustrator.<ref name=dnb/> Many of his commissions for illustrations came from the publisher [[John Lehmann]]. Both men were homosexual, and they were so much in one another's company that some people supposed that they were partners, though the biographer [[Artemis Cooper]] thinks it unlikely.<ref>Cooper, p. 152</ref> For Lehmann, Minton illustrated ''[[A Book of Mediterranean Food]]'' and ''[[Elizabeth David bibliography#French Country Cooking (1951)|French Country Cooking]]'' (the first two books by the food writer [[Elizabeth David]]), travel books such as ''Time was Away – A Notebook in Corsica'', by [[Alan Ross]], and fiction, including ''Treasure Island'' by [[Robert Louis Stevenson]].<ref name=dnb/><ref name=MSalisbury>{{cite web |author=Martin Salisbury|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2017/oct/21/cover-stories-beautiful-book-jacket-designs-in-pictures|title=Cover stories: beautiful book-jacket designs - in pictures |date=21 October 2017|accessdate=24 October 2017|work=The Observer}}</ref> He also produced dustwrappers for many publishers including [[Michael Joseph (publisher)|Michael Joseph]], [[Secker and Warburg]] and [[Rupert Hart-Davis]]. One such notable book jacket was for [[H. E. Bates]] ''The Country Heart'' (Michael Joseph 1949).<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Country Heart :: HE Bates|url=https://hebates.com/library/the-country-heart|access-date=2021-10-17|website=hebates.com}}</ref> |

Minton's posthumous fame is principally as an illustrator.<ref name=dnb/> Many of his commissions for illustrations came from the publisher [[John Lehmann]]. Both men were homosexual, and they were so much in one another's company that some people supposed that they were partners, though the biographer [[Artemis Cooper]] thinks it unlikely.<ref>Cooper, p. 152</ref> For Lehmann, Minton illustrated ''[[A Book of Mediterranean Food]]'' and ''[[Elizabeth David bibliography#French Country Cooking (1951)|French Country Cooking]]'' (the first two books by the food writer [[Elizabeth David]]), travel books such as ''Time was Away – A Notebook in Corsica'', by [[Alan Ross]], and fiction, including ''Treasure Island'' by [[Robert Louis Stevenson]].<ref name=dnb/><ref name=MSalisbury>{{cite web |author=Martin Salisbury|url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/gallery/2017/oct/21/cover-stories-beautiful-book-jacket-designs-in-pictures|title=Cover stories: beautiful book-jacket designs - in pictures |date=21 October 2017|accessdate=24 October 2017|work=The Observer}}</ref> He also produced dustwrappers for many publishers including [[Michael Joseph (publisher)|Michael Joseph]], [[Secker and Warburg]] and [[Rupert Hart-Davis]]. One such notable book jacket was for [[H. E. Bates]] ''The Country Heart'' (Michael Joseph 1949).<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Country Heart :: HE Bates|url=https://hebates.com/library/the-country-heart|access-date=2021-10-17|website=hebates.com}}</ref> |

||

Although Minton was respected both by the conservative [[Royal Academy]] and the modernist [[London Group]],<ref name=mg/> he was out of sympathy with the [[abstract painting]] that began to prevail during the 1950s, and he felt increasingly out of touch with current fashion. He suffered extreme mood swings and became dependent on alcohol. In 1957, he took an overdose of sleeping tablets to take his own life at home,<ref name=dnb/> 9 Apollo Place, [[Chelsea, London]], and died on the way to St Stephen's Hospital, Chelsea. He left an estate valued at £13,518 |

Although Minton was respected both by the conservative [[Royal Academy]] and the modernist [[London Group]],<ref name=mg/> he was out of sympathy with the [[abstract painting]] that began to prevail during the 1950s, and he felt increasingly out of touch with current fashion. He suffered extreme mood swings and became dependent on alcohol. In 1957, he took an overdose of sleeping tablets to take his own life at home,<ref name=dnb/> 9 Apollo Place, [[Chelsea, London]], and died on the way to St Stephen's Hospital, Chelsea. He left an estate valued at £13,518, worth £416,997 in 2023. |

||

==Memorials== |

==Memorials== |

||

| Line 47: | Line 46: | ||

==References== |

==References== |

||

{{reflist |

{{reflist}} |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

| Line 60: | Line 59: | ||

* {{Art UK bio}} |

* {{Art UK bio}} |

||

{{Subject bar|commons=yes|commons-search=Category:John Minton|q=yes|d=yes|d-search=Q6248972}} |

{{Subject bar|commons=yes|commons-search=Category:John Minton|q=yes|d=yes|d-search=Q6248972}} |

||

* [https://collections.rafmuseum.org.uk/collection/object/object-5723 The Winged Life (book cover design) by John Minton] (circa 1953) at The [[Royal Air Force Museum London]]. |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

| Line 66: | Line 65: | ||

[[Category:1917 births]] |

[[Category:1917 births]] |

||

[[Category:1957 suicides]] |

[[Category:1957 suicides]] |

||

[[Category:1957 deaths]] |

|||

[[Category:20th-century English painters]] |

[[Category:20th-century English painters]] |

||

[[Category:Academics of Camberwell College of Arts]] |

[[Category:Academics of Camberwell College of Arts]] |

||

[[Category:Academics of the Central School of Art and Design]] |

[[Category:Academics of the Central School of Art and Design]] |

||

[[Category:Alumni of St John's Wood Art School]] |

[[Category:Alumni of St John's Wood Art School]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:Artists who died by suicide]] |

||

[[Category:English conscientious objectors]] |

[[Category:English conscientious objectors]] |

||

[[Category:English illustrators]] |

[[Category:English illustrators]] |

||

[[Category:English male painters]] |

[[Category:English male painters]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:English gay artists]] |

||

[[Category: |

[[Category:British landscape artists]] |

||

[[Category:English LGBT |

[[Category:English LGBT painters]] |

||

[[Category:Gay painters]] |

|||

[[Category:Suicides in Chelsea]] |

[[Category:Suicides in Chelsea]] |

||

[[Category:People educated at Reading School]] |

[[Category:People educated at Reading School]] |

||

| Line 83: | Line 84: | ||

[[Category:Royal Pioneer Corps soldiers]] |

[[Category:Royal Pioneer Corps soldiers]] |

||

[[Category:Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry officers]] |

[[Category:Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry officers]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century LGBT people]] |

[[Category:20th-century English LGBT people]] |

||

[[Category:Drug-related suicides in England]] |

[[Category:Drug-related suicides in England]] |

||

[[Category:20th-century English male artists]] |

[[Category:20th-century English male artists]] |

||

[[Category:Military personnel from Cambridgeshire]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 19:10, 26 April 2024

John Minton | |

|---|---|

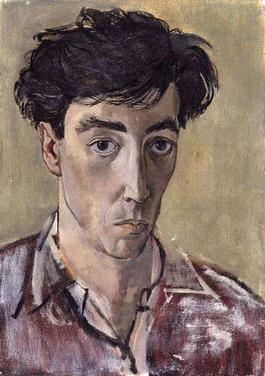

Self-portrait c.1953 | |

| Born | 25 December 1917 Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire, England |

| Died | 20 January 1957 (aged 39) Chelsea, London, England |

| Education | St John's Wood School of Art |

| Known for | Painting, illustration |

Francis John Minton (25 December 1917 – 20 January 1957) was an English painter, illustrator, stage designer and teacher. After studying in France, he became a teacher in London, and at the same time maintained a consistently large output of works. In addition to landscapes, portraits and other paintings, some of them on an unusually large scale, he built up a reputation as an illustrator of books.

In the mid-1950s, Minton found himself out of sympathy with the abstract trend that was then becoming fashionable, and felt increasingly sidelined. He suffered psychological problems, self-medicated with alcohol, and in 1957 died by suicide.

Life and career[edit]

Early years[edit]

Minton was born in Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire, the second of three sons of Francis Minton, a solicitor, and his wife, Kate, née Webb.[1] From 1925 to 1932, he was educated at Northcliff House, Bognor Regis, Sussex, and then from 1932 to 1935 at Reading School.[1] He studied art at St John's Wood School of Art from 1935 to 1938[2] and was greatly influenced by his fellow student Michael Ayrton, who enthused him with the work of French neo-romantic painters.[1] He spent eight months studying in France, frequently accompanied by Ayrton, and returned from Paris when the Second World War began.

In October 1939 Minton registered as a conscientious objector, but in 1941 changed his views and joined the Pioneer Corps. He was commissioned in the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry in 1943, but was discharged on medical grounds in the same year.[1] While in the army, Minton, with Ayrton, designed the costumes and scenery for John Gielgud's 1942 production of Macbeth. The settings moved the piece from the 11th century to "the age of illuminated missals";[3] The Manchester Guardian wrote that they "should be long remembered".[2] In the same year he and Ayrton held a joint exhibition at the Leicester Galleries in London. The Times wrote, "Mr. Minton is seen to have an overcast, gloomy realism, and much intensity of feeling, which he expresses in dark colour schemes, both in a curious and effective self-portrait and in paintings of streets and bombed buildings."[4] Minton's early penchant for dark colour schemes can be seen in his 1939 Landscape at Les Baux, in the Tate Gallery.[5]

Teacher, painter and illustrator[edit]

From 1943 to 1946 Minton taught illustration at the Camberwell College of Arts, and from 1946 to 1948 he was in charge of drawing and illustration at the Central School of Art and Design.[6] At the same time he continued to draw and paint, sharing a studio for some years with Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, and later with Keith Vaughan.[1] Reviewing a 1944 exhibition, The Times remarked that Minton was clearly in the tradition of Samuel Palmer,[7] something frequently remarked on by later critics.[1][6] Minton's output was considerable. Between 1945 and 1956 he had seven solo exhibitions at the Lefevre Gallery, notwithstanding his work as tutor to the painting school of the Royal College of Art in 1949, a post that he held until the year before his death.[6] Minton's appearance in this period is shown in a 1952 portrait by Lucian Freud,[8] as well as in self-portraits. In the 1940s he, Freud and fellow artist Adrian Ryan had been in a homosexual love triangle.[9]

Every living person has certain feelings about the world around him. It is these feelings, common to all men, which are the raw materials of the artist's inspiration. This he must 'translate', into the structure of an art form, whether music, poetry or painting. The problem of the painter is this 'translation'; that is, he has to create some arrangement of shape, line and colour which convey the idea or the emotion which moved him to paint this particular picture.

John Minton, 1949[10]

Minton's range was wide. Although he is best remembered as an illustrator, he also worked on a very large scale, with unusually big paintings for the Dome of Discovery at the Festival of Britain and "two vast set-pieces" for the Royal College of Art,[6] and at the Royal Academy a huge painting of the soldiers dicing for the garment of Jesus, described by The Manchester Guardian as "one of the most elaborate and serious paintings with a religious theme produced since the war."[2]

He designed textiles and wallpapers;[2] he produced posters for London Transport and Ealing Studios; and he was highly regarded as a portrait painter.[1] He also worked in collage.[11] He painted scenes of Britain, from rural beauty to urban decay, and travelled overseas, producing scenes of the West Indies, Spain and Morocco. The Times wrote, "Even when they were ostensibly of Spain and Jamaica, Minton's landscapes looked back to Samuel Palmer for their mood. They were densely patterned and luxuriantly coloured, and it was always the fullness and richness of the scene which attracted his eye and which he painted with such evident enjoyment."[6]

Minton's posthumous fame is principally as an illustrator.[1] Many of his commissions for illustrations came from the publisher John Lehmann. Both men were homosexual, and they were so much in one another's company that some people supposed that they were partners, though the biographer Artemis Cooper thinks it unlikely.[12] For Lehmann, Minton illustrated A Book of Mediterranean Food and French Country Cooking (the first two books by the food writer Elizabeth David), travel books such as Time was Away – A Notebook in Corsica, by Alan Ross, and fiction, including Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson.[1][13] He also produced dustwrappers for many publishers including Michael Joseph, Secker and Warburg and Rupert Hart-Davis. One such notable book jacket was for H. E. Bates The Country Heart (Michael Joseph 1949).[14]

Although Minton was respected both by the conservative Royal Academy and the modernist London Group,[2] he was out of sympathy with the abstract painting that began to prevail during the 1950s, and he felt increasingly out of touch with current fashion. He suffered extreme mood swings and became dependent on alcohol. In 1957, he took an overdose of sleeping tablets to take his own life at home,[1] 9 Apollo Place, Chelsea, London, and died on the way to St Stephen's Hospital, Chelsea. He left an estate valued at £13,518, worth £416,997 in 2023.

Memorials[edit]

A major exhibition to mark Minton's centenary took place at Pallant House Gallery in Chichester from 1 July to 1 October 2017, co-curated by the Gallery's Director Simon Martin and Minton's biographer Frances Spalding, and is the first exhibition in a museum since the 1994 touring Select Retrospective.[15]

Minton was the subject of the song "The Ghost of Mr. Minton" by London-based pop group Would-Be-Goods on their 2008 album Eventyr. A quote from Minton, "We're all awash in a sea of blood, and the least we can do is wave to each other" inspired the title of the Van der Graaf Generator album The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other.[16]

In the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography's entry on Minton, Michael Middleton writes:

Minton is often seen as an illustrator rather than a painter. He certainly extended and enriched the English graphic tradition. In all his varied output, however, may be sensed an elegiac awareness of the evanescence of physical beauty that is entirely personal. His work is to be found in the Tate collection, and many public and private collections at home and abroad. A retrospective exhibition of 1994, curated by his biographer, Frances Spalding, provided a convincing reminder of the range of his gifts. For the historian he must remain a potent symbol of his period.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Middleton, Michael. "Minton, (Francis) John (1917–1957)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, online edition, Oct 2006, accessed 16 May 2011 (subscription required)

- ^ a b c d e Bone, Stephen. "John Minton – Artist of many talents," The Manchester Guardian, 22 January 1957, p. 5

- ^ "Macbeth", The Times, 9 July 1942, p. 6

- ^ "Young Artists – Exhibition at Leicester Galleries", The Times, 16 October 1942, p. 6

- ^ "Landscape at Les Baux", Tate Collection, accessed 25 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d e "Mr. John Minton – The lyrical touch," The Times, 22 January 1957, p. 12

- ^ "Art Exhibitions – Early Calm and Modern Unrest", The Times, 25 October 1944, p. 6

- ^ "John Minton 1952". Archived from the original on 9 November 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ^ Brown, Mark (10 July 2021). "Exhibition brings to light young Freud's love triangle". The Guardian. London. p. 25.

- ^ Minton, John. "Seven Artists Tell why they Paint", Picture Post, 12 March 1949. p. 13

- ^ "Antiques Roadshow - Series 42: Morden Hall Park 2". BBC. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- ^ Cooper, p. 152

- ^ Martin Salisbury (21 October 2017). "Cover stories: beautiful book-jacket designs - in pictures". The Observer. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "The Country Heart :: HE Bates". hebates.com. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- ^ "Pallant House Gallery". Archived from the original on 24 April 2017.

- ^ The Least We Can Do Is Wave to Each Other (additional poster) (Media notes). Charisma Records. 31 December 1969. CAS 1007. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

Further reading[edit]

- Salisbury, Martin (2017). The Snail that climbed the Eiffel Tower and other work by John Minton. Norwich: The Mainstone Press. ISBN 978-0-9576665-3-5.

- Cooper, Artemis (2000). Writing at the Kitchen Table – The Authorized Biography of Elizabeth David. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 0-7181-4224-1.

- *Spalding, Frances (1991). Dance till the stars come down: A biography of John Minton. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-340-48555-8.(Reprint 2005 as John Minton: Dance till the stars come down) Lund Humphries, ISBN 0-85331-918-9)

- Spalding, Frances (1994). John Minton 1917–1957: A selective retrospective. London: Royal College of Art. ISBN 1-870797-13-2.

- Rigby Graham, 'John Minton as a Book Illustrator', in The Private Library; 2nd series 1:1 (1968 Spring), p. 7-36

- John Lewis, 'Book Illustrations by John Minton', in Image; 1 (1949 Summer), p. 51-62

External links[edit]

- 53 artworks by or after John Minton at the Art UK site

- The Winged Life (book cover design) by John Minton (circa 1953) at The Royal Air Force Museum London.

- 1917 births

- 1957 suicides

- 1957 deaths

- 20th-century English painters

- Academics of Camberwell College of Arts

- Academics of the Central School of Art and Design

- Alumni of St John's Wood Art School

- Artists who died by suicide

- English conscientious objectors

- English illustrators

- English male painters

- English gay artists

- British landscape artists

- English LGBT painters

- Gay painters

- Suicides in Chelsea

- People educated at Reading School

- People from Great Shelford

- British Army personnel of World War II

- Royal Pioneer Corps soldiers

- Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry officers

- 20th-century English LGBT people

- Drug-related suicides in England

- 20th-century English male artists

- Military personnel from Cambridgeshire